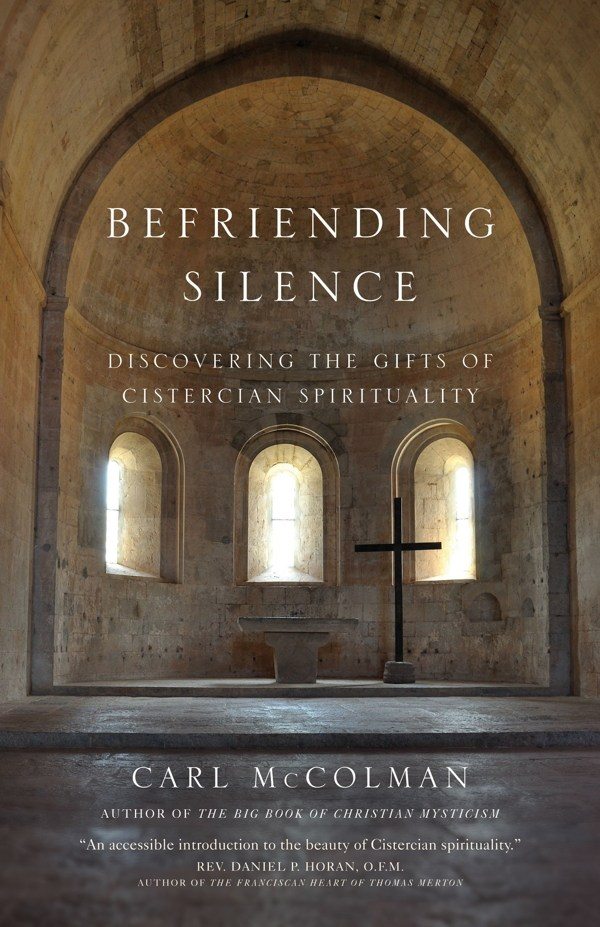

Interview with Carl McColman on Befriending Silence: Discovering the Gifts of Cistercian Spirituality

Interview with Carl McColman, January 2016

facilitated by Colette Lafia

Carl McColman and I share a mutual appreciation and affection for the monastic life. We first connected last year when he read and reviewed my book, Seeking Surrender: How a Trappist Monk Taught me to Trust and Embrace Life. Now, I am delighted to return the honor by introducing you to his wonderful new book.

Befriending Silence: Discovering the Gifts of Cistercian Spirituality, published in November (2015) by Ave Maria Press, is a celebration of the wisdom that monastic life holds for all of us.

Carl is a contemplative writer, speaker, and retreat leader. He is the author of several books, as well as an avid blogger. To learn more about Carl and his work, please visit his website at: http://www.carlmccolman.net.

Befriending Silence is written with the hospitality one feels when visiting a monastery. The book is very accessible—it’s personal at times and challenging at others, yet is always encouraging. I highly recommend it, and will continue to draw on it as a resource for my own spiritual growth and teaching.

Q: The title of your book, Befriending Silence, is so welcoming. It invites the reader to become friends with silence—with something that might feel unfamiliar, strange, and even a little intimidating. What does befriending silence mean to you?

Most of the universe is vast, open space — silent space. And when you consider that even matter is composed mostly of “trapped energy” that is no more substantial than butterflies frolicking in a cathedral, then literally everything — including you and me — is composed mostly of silent space. So silence is knit into the very fabric of being. Thomas Keating calls silence, “God’s first language,” and the first verse of Psalm 65, which is often mistranslated, in the original Hebrew literally says, “Silence is praise.”

In fact, silence is linked to intimacy with God throughout the Hebrew scriptures. Habakkuk proclaims, “the Lord is in his holy temple; silence before him, all the earth!” And in I Kings, the presence of God is described as “a light silent sound” (other Bible translations say “a sound of sheer silence” or “a still small voice”). So silence is linked to the presence of God. As our society gets noisier and noisier, monks and nuns are serving as custodians for silence: for many people, going to a monastery is really the only way they can encounter deep silence.

So to answer your question, to me “befriending silence” means re-discovering something that is already deep within us, something gentle, serene, and filled with the luminous presence of God.

But we have to learn how to befriend silence because we have been so conditioned to live in our noisy world that for many of us, silence at first can seem scary or unsettling. But that’s because we’re not used to it. When we allow ourselves to rest in silence, we discover its beauty and its radiance. That, to me, is the heart of befriending silence.

Q: Can you talk about your own journey with silence? How do you integrate silence into both an active work life and married life?

I’m a child of the 60s and 70s, so the soundtrack of my youth was rock and roll: the Beatles, Led Zeppelin, Yes, the Grateful Dead. TV was always on in my childhood home, and I’ve owned a personal computer since 1984. So like most people of my generation, silence is something I had to discover. As a child, I loved to read, so I enjoyed visiting the library, which back then especially was still a haven of silence. And my family was conventionally religious — I was raised Lutheran — so I learned early on that churches were often silent (sadly, that seems to be less and less true nowadays).

But my first really meaningful encounter with silence was the first time I participated in a quiet day, at the Shalem Institute in Washington, DC in the mid 1980s. I found that I truly loved the beauty of being intentionally silent with other spiritual seekers. Shalem is where I first was introduced to the practice of intentional silence as prayer — a practice that has remained with me for over 30 years now. Later on, I started visiting monasteries, and have been nourished by intentional silence ever since.

As for integrating silence into my work and marriage life, I see it slightly differently: the question really is, how do we integrate our activities into the silence that is always already there?

Carl McColman, July 2013. Photo by Fran McColman.

For me, and I imagine for most people, I need a daily time of intentional silent prayer to remind me that silence is always present, always upholding me and my activities, no matter how noisy the momentary circumstances of my life might be.

I am tremendously blessed in that my wife is also very much a contemplative and loves to sit in silent prayer with me. And because my ministry is all about sharing Christian contemplation and interfaith dialogue with others, silence is a natural part of everything I do. Again, I’m very blessed. But even so, I need those daily times of intentional silence, to keep me “calibrated” as it were. I really notice it when I miss my daily silence.

Q: How do you see that this book could be a companion for someone who wants to explore and engage in monastic practices such as reading The Divine Office, practicing Lectio Divina, and inviting more silence and contemplation into one’s spiritual life?

In many ways that is really the heart of the book. The story behind the book is that when I made my life profession as a Lay Cistercian in 2012, I blogged about it, and an editor with my publisher read my blog and reached out to me. We began a conversation about Cistercian spirituality and how it can bless those of us who are not necessarily called to be monks or nuns. This book is the fruit of that conversation. Perhaps the central metaphor of the book is gift — it’s in the subtitle, and really is based on how Cistercians describe their own identity: as the “Cistercian charism,” or the gift of this particular spirituality.

And I believe very strongly that the elements of the Cistercian way of life really are gifts: gifts from God, given to the monks and nuns, of course, but also available to all of us, for God is a cheerful, lavish giver.

Now, you mention monastic practices: lectio divina, the Divine Office, the vows such as stability and fidelity, that sort of thing. Obviously, for monks, these practices are central for their way of life. For non-monks, however, they are “optional” — no one is going to be frowning at us if we don’t bother to recite Morning Prayer. But what I try to convey in the book is that these practices are the ways in which we can more fully receive and integrate the spirituality of the Cistercians into our lives. The fancy word here is formation: we are created in the image and likeness of God, meaning we have a basic goodness and dignity about us. But unfortunately it has been marred by sin, narcissism, fear, wounding and being wounded — none of us are perfect, we all have been hurt and if we are honest we will admit that we all do hurtful things, too, even if we don’t want or intend to.

So the spiritual journey is a process of forming (or perhaps re-forming) that authentic image and likeness within us. We respond to the love of God (Divine Love) and seek to be love in our own lives. The monastic practices are tools to help us in that formative process. Of course, it’s the Holy Spirit who does the forming: our job is to cooperate, not to run the show.

Q: What surprised you in the course of writing this book? What did you discover? What deepened in you?

Carl McColman, March 2004. Photo by Matt Jones.

What a thoughtful question. As you may know, I did the bulk of the writing of this book in 2014, beginning in the spring and wrapping it up by the end of the year. In the midst of all that, my daughter Rhiannon was dying from a lifelong struggle with kidney disease — she entered in-home hospice in January 2014 and passed away at the end of August.

So I think what really surprised me more than anything else was how writing this book really blessed and supported me during Rhiannon’s illness and passing — and how being her companion in hospice and death really made me that much more aware of how much Cistercian spirituality is a blessing.

You know, monks (at least the ones I know) are not morbid or dour — they tend to be happy, even merry people. But they are not afraid of death. Their funeral rites are very simple and matter-of-fact. They have profound, real (not feigned) trust in the love and mercy of God. So I think my surprise and my deepening came from discovering how monastic spirituality is not afraid of death, and that it can help us to accept death, as well — and conversely, how experiencing the death of a loved one helped me to understand the Cistercian charism better.

Q: So much of your book is about the journey of learning to live in the heart and from the heart. Is this a central theme you were exploring?

One of the interesting things I’ve learned about being a writer is that it seems our writing operates on both a conscious and a sub-conscious (or maybe super-conscious or trans-conscious?) level. For me, the conscious metaphor for this book was gift, as I mentioned, and also Bernard of Clairvaux’s three steps of truth: humility, compassion and contemplation. But now that the book is published, and other people are reading it, I expect I will learn all the themes that dance through the book even beyond what I was consciously planning. So that’s the reality of the “heart” theme, which now that you point it out I can see is very much a part of the book. But it wasn’t something I consciously set out to do!

Now, on the other hand, the heart is very much a theme of my writing and speaking ministry in general, so I think that’s part of what’s going on here. As you know, Orthodox Christians have a long history of viewing contemplation as “prayer of the heart,” which is a way of describing the Jesus Prayer. In the Jesus Prayer (and really in all forms of silent or contemplative prayer) we give the mind a rest and pray more fully from the heart. But I think it’s important to remember that this isn’t just about the blood-pump in our chests (as precious and important as the heart is). Really, “heart” is a code-word for the body as a whole.

Contemplative prayer is embodied prayer, prayer that pays attention to posture, to breathing, to relaxation. We pray with our bodies. We don’t just “have” bodies, we are bodies. We are incarnate: embodied creatures.

The body is a great gift, but thanks to a number of cultural currents (Greek dualism, Cartesian philosophy, and so forth) many of us see “body” and “spirit” as somehow opposed or at odds. Yet monastic spirituality is an embodied spirituality. The monks don’t just pray and meditate together, they also work and eat together, care for one another when they are sick, grow their own food, and acknowledge the goodness and dignity of labor. So especially living as we do in a time of ecological crisis, we all need to more fully celebrate our essential embodiment, and monastic spirituality is a great way to do that.

Embodied spirituality is heart spirituality: it’s really that simple.

Q: In your book, you’re willing to touch upon some rather demanding and unfashionable concepts, like obedience, humility, and being a sinner, or as you put it, “someone wounded and always under construction.” How important do you think it is that we challenge ourselves to remain open to fully facing these aspects of our life and spirituality? And how can we do that in our daily lives?

It’s very interesting being a Catholic writer today: there are those who think that the old language of sin, repentance, asceticism, etc. is dysfunctional and needs to be abandoned, and there are others who think that part of the problem with the Church and society is that we don’t used those traditional concepts enough! So I try to write in a way that can speak to that entire spectrum. I really do believe that sin exists: how else do we explain Daesh or the Shoah? Or even just all the violence and addiction and selfishness and narcissism that touches just about every life in one way or another? Face it, we human beings hurt one another, and we hurt ourselves. Maybe some of us, thanks to social privilege and lots of good therapy, get to the point where our destructive tendencies are “in remission,” but I think the cancer is still there.

But it’s so important to keep this in perspective! We are created in the image and likeness of God. We are not bad people, we are good people who sometimes do bad things. And we need God’s grace and mercy to undo the damage, not only to our relationships but also to our selves. So I do think it’s important to look at some of these “old-fashioned” concepts, but we also have to do so with a discerning mind and heart. Sometimes the language of sin and obedience has been used to oppress people, especially those who historically have been seen as “other” in the eyes of the Church: women, Jews, slaves, gays and lesbians. When a mystic obeys God it is holy, but when a slave obeys a master it is victimization. We need to be clear about this, about how our religious language sometimes carries unhealthy baggage. But with that clarity, then we are in a better position to reclaim the spiritual genius at the heart of much of this traditional language.

Take “humility” for example: our secular world rejects the idea of humility: we’re supposed to be “looking out for #1” and “winning through intimidation” (those are actual titles of self-help books). But humility is a grace. It’s not the same thing as humiliation or abnegation which is how it gets mis-interpreted.

True humility is more akin to earthiness and lack of narcissism. Those are good qualities, holy qualities, qualities that everyone needs, but unfortunately our secular world has forgotten this — so we have to turn to the monks to remember these gifts.

Q: Your book is so accessible and inviting that anyone interested in the spiritual life can find something of value in it. How can we all benefit from the qualities inherent in monastic life: simplicity, humility, prayer, and old-fashioned hard work?

What I’m tempted to say is “try it and see!” Monastic spirituality is truly countercultural. I mentioned that I grew up listening to the Grateful Dead, and we had this idea that we (the deadheads) were the “counterculture” because we rejected the crass materialism of society at large. But it was really a shallow counterculture: many of us grew up and joined the very society that as youths we scorned. As Don Henley sang, “the other day I saw a deadhead sticker on a Cadillac” — in other words, how quickly we abandoned our countercultural ideals as soon as we got nice paying jobs.

But monastic spirituality is an authentic counterculture: it’s not about the clothes we wear or the concerts we attend, it’s about a genuinely alternative way of life. Obviously, monks and nuns take this all the way; but even those of us who aren’t called to live in the cloister can give ourselves, in some measure, to this way of life that puts silence before noise, relationships before belongings, love before fear, hope before cynicism, simplicity before stress.

I’m not saying that everyone has to get rid of all their money in order to be spiritual! That’s not the point — the point is learning genuine non-attachment, cultivating real humility and compassion, and trusting in God rather than Wall Street to provide for us. For many people the resulting changes may be very small and barely noticeable, but I believe that over time they will yield huge spiritual blessings — not only for ourselves, but for our family, friends, neighbors and community, as well.

Going back to my deadhead analogy: I think the problem with secular countercultures is that they’re based on rejection, hatred, contempt: rejecting wealth, hating the “1%,” having contempt for mainstream values. But monastic spirituality is countercultural not because of what it rejects, but because of what it embraces: God, love, mercy, forgiveness, humility, simplicity, silence. We are defined by what we love, not by what we hate. That’s why it’s not a contradiction to be a spiritual person and also have wealth (although I do believe that a genuinely spiritual person who is blessed with abundance will manage and use their wealth in different ways than others might, who lack a spiritual orientation).

Q: Now that the book is out in the world, what is your biggest hope for it?

Well, I suppose like any author I want my book to reach everyone who might be blessed by it (and I think that would include just about everyone). So I hope it finds a wide readership, even though realistically a book like this will tend to have a small and focused audience. But that’s okay. The rudder of an ocean liner is very small, yet it steers the entire vessel.

I think those of us who are called to a contemplative spirituality are like the rudder of an ocean liner. We are small in numbers, but if we are faithful to our task to love God, love our neighbors as we love ourselves, and even love our enemies, then we will be pouring blessings into the world, simply by being true to who we are called to be.

And we will have a huge impact, even though it may start small and not really be visible until generations after we are gone. Another analogy is the olive tree: many varieties of olives do not bear fruit until the tree is decades old. So when someone plants that kind of an olive tree, she or he is giving a gift to their children or grandchildren. I think contemplative spirituality works the same way.

God is a patient God, a God of eternity as well as time. We are used to worldly values where everything is about the immediate bottom line, visible results, having an impact right here and right now. But the ways of God are subtler, quieter, and built to last, so they take longer to mature. We are called to be faithful, which may or may not look “successful” or “powerful.”

So my hopes for the book are along these lines. I hope people who need it or will be blessed by it manage to find it, and read it, and hopefully it will be a gift for them. And then I hope they pass it on to someone else and just try to live a faithful life. The book itself is not that important! But the invitation is: the invitation to respond to the lavish, vast, radiant love of God, and to let that love shape our lives and guide our path.

Now, having said all that, I have one other hope: I hope that somebody whose heart is shaped for the Cistercian charism, when they read this book, will respond in the way that is appropriate for them. For many people, that might mean just learning to pray and love and pay attention to silence. Others might want to formally join a Lay Cistercian community. And some may even discern a call to become monks or nuns. If, by the grace of God, my book can help a young man or woman on their journey to discern a call to religious life, I would just be so honored.

Other books by Carl include:

- The Big Book of Christian Mysticism, cover design by Tracy Johnson.

- Answering the Contemplative Call. Cover design by Barbara Fisher.

What a wonderful interview!

You couldn’t know, but you are helping me!

I don’t know if I will read the book now, I fear I can’t understand and lose myself in the dictionary to translate in my native language.

But I can understand this article and it is very very near to my goal: not slave, not humiliation, but a true spirituality, with a clear awareness.

Good luck!

Just finished reading this interview… and feel so very graced by so much that McColman has shared. I feel encouraged to stay the contemplative path and allow the Holy Spirit to continue the re-forming process. i look forward to reading this book and reflecting on how Monastic life might further inform my journey into God.

Thank you for such an insightful interview. deeply enjoyed it!

Be Graced