Interview with Jonathan Montaldo

Interview with Jonathan Montaldo, November 2015

facilitated by Colette Lafia

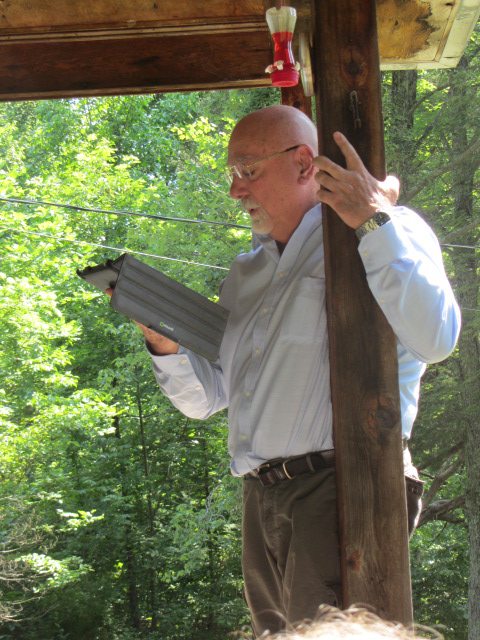

I had the great joy of meeting Jonathan Montaldo twelve years ago at the Santa Sabina Center in San Rafael, California, when he led a retreat based on the teachings of Thomas Merton. Over the years we have shared a friendship, and I’m grateful that our lives and paths connected. When I was writing Seeking Surrender, which was centered around my friendship with Brother René at the Abbey of Gethsemani in Kentucky, Jonathan encouraged and supported my project.

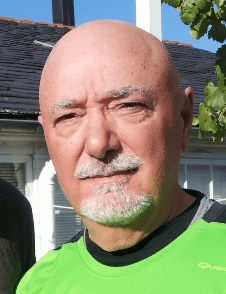

Jonathan Montaldo is a leading Thomas Merton scholar. He’s edited numerous volumes of Merton’s writing and served as past director of the Thomas Merton Center at Bellarmine University in Kentucky, which contains the largest archive of Merton’s work. 2015 has been a busy year for him and his colleagues, who contributed in many venues to celebrating Merton’s centenary (1915 -2015). Find out more about his work and books at www.MonksWorks.com.

Jonathan Montaldo is a leading Thomas Merton scholar. He’s edited numerous volumes of Merton’s writing and served as past director of the Thomas Merton Center at Bellarmine University in Kentucky, which contains the largest archive of Merton’s work. 2015 has been a busy year for him and his colleagues, who contributed in many venues to celebrating Merton’s centenary (1915 -2015). Find out more about his work and books at www.MonksWorks.com.

Jonathan turned seventy on October 4th of this Merton centennial year celebration. He has told me that he senses he is entering his “holy seventies,” and the playfulness of his remark made me want to learn more. I requested a written interview and conversation about his life and his work as a Merton scholar. I sent him my questions in an email. He had just finished presenting a retreat in Assisi, Italy, on November 4th, and afterwards he wrote his responses from Rome, as he waited to fly to Sweden to present four papers during a Merton Symposium sponsored by the Ecumenical Community of Bjärka-Saby, monastics who are mostly Pentecostals.

This event in Sweden (he will live with this unusual monastic community for three weeks) will end Jonathan’s activities celebrating Merton’s centenary year, during which the monk was “elevated” to recognition by Pope Francis, in his address before the United States Congress on September 24th. The Pope described Merton as “a man of prayer, a thinker who challenged the certitudes of his time and opened new horizons for souls and for the Church. He was also a man of dialogue, a promoter of peace between peoples and religions.” He then went on, likening himself to Merton as a “builder of bridges” through dialogue to help overcome historic differences between people and their religious traditions.

Of all your Merton projects, what are your favorites—the ones of which you are most proud?

I have read Merton since I was a boy of thirteen, an interest sparked by an older cousin’s entry into Trappist-Cistercian monastic life at Saint Joseph’s Abbey in Spencer, Massachusetts. I picked up his autobiography, The Seven Storey Mountain, from my Uncle Bert’s bedside table and my heart was “bitten.” I remember reading next a book of photographs of monks living in the 12th-century monastery, Pierre que Vire, in France, for which Merton had written the Introduction. This book, Silence in Heaven, presented Merton’s view of monastic life at its most romantic with professional and arty photos of the monks, including the very young ones. Seeing boys only a few years older than me, clothed in white cowls at Mass with the light from altar candles shining in their faces, I heard a “call” and wanted to be in that picture. A Jungian would have a field day, especially were I to go on about what Merton’s words and those beautiful pictures awakened in me, a dimension of my soul that I have never lost throughout my curved journey through life.

In some deep way I, myself, cannot fathom, I remain—reaching seventy—that pious boy wanting to love God in a monastic community.

Entering religious life at seventeen, after five years of studying to be a Jesuit in the New Orleans province, I departed the Society, reluctantly, as I was too immature to realize that there might have been an integral and righteous way for me to be both gay and a Jesuit priest. I renounced my vows on December 8, 1967, at 22, hoping to grow up. I distanced myself from a vocation that I loved and was actually called to (I understand that now) by naming my immature attempt as an “immaculate misconception.”

Drafted out of graduate school, I joined the Navy but went to Da Nang, Vietnam, anyway, serving on Freedom Hill, one of two Navy guys on a Marine base. We kept our noses clean and hid in the shadows, knowing we might more easily be killed in the cross-fire of marines fighting one another than harmed by North Vietnamese. I was stationed in Virginia, and then for two and a half glorious years in Naples, Italy, before I received my Masters Degree in Theology and Literature from Emory University, with a thesis on Merton: “Toward the Only Real City in America: Paradise and Utopia in the Autobiography of Thomas Merton.” I was twenty-nine and typing library cards so as to eat during my studies, so I decided not to take the Ph.d., but find a job to keep myself together. This was in 1974.

In 1986—sparing you details of my life as a rolling stone—some friends finally realized I was going nowhere quickly and urged me to join them in a business, which after seven years found me financially very well-off. After that, I took a sabbatical year of light duties at my business and took up a project for Robert Daggy at the Thomas Merton Center at Bellarmine, in Louisville.

Using Xeroxes and working on a typewriter back in New Jersey where I was living, I produced facsimile copies of four of Merton’s working notebooks, which hardly anyone could read (there were fifty-one of these “reading notebooks” in Bellarmine’s collection alone). I provided footnotes and bibliographies of the books he was reading, and got them over to Bob Daggy—to his delight.

Brother Patrick Hart, who had been my friend since I did research at Gethsemani for my thesis, in 1974, was equally impressed. And when he was appointed the General Editor of Merton’s complete journals to be published by HarperSanFrancisco in seven volumes, inquired if I were interested in editing the second volume, which became Entering the Silence: Becoming a Monk and a Writer. I peed my pants and said, “Why, sure.” Thus began my road through serving Merton’s legacy until now. Every Christmas, I send Brother Patrick a card in which I express, once again, that he is the father of my mature and true vocation. He picked me up out of nowhere and set me to work on what, in retrospect, it seems I was born to accomplish.

Turning seventy last month, I sense that I must slowly abandon the raft that Merton’s texts have provided me to cross the river of my life.

In a sense, while I have written on Merton in essays and introductions to my editions of his books, I have never spoken in my own voice, writing very early that I knew editors must efface themselves behind their authors.

I’ve been asked more than once where Merton stops and I begin. I’m certainly over-identified with Merton’s journey to seek God in the monastic life, but I never wanted to meet Merton at Gethsemani. Friends of mine did, but I did not envy them. I wasn’t interested in shaking his hand.

Even at the Merton Center, when I took his private journals into my own hands, it was not Merton that brought tears to my eyes, but his texts through which I have a found a place to live, move, and have my being. Heart has spoken to heart, but only in the texts, the words, the gestures he communicated to me of a way forward to a kind of life I had dreamed about as a boy.

At a recent meeting of the Merton British Society at Oakham, the four plenary speakers were asked why they were interested in Thomas Merton. When it was my turn, I said that Merton had been a raft for me, but as the Buddha taught, once you have cobbled together, of many materials, a raft for yourself to cross a river without bridges or ferries, you must set the raft down and walk forward on your own two feet. Saying this, I wept in front of the mostly British crowd—I can only imagine their horror at this display of bad form.

Since 2012, when I said it publicly, I have repeated this intuition many times until one of my friends had more than enough and told me, “Listen, man, you’re still clinging to your Merton raft, you’re just realizing that you and your raft are heading toward the falls. Enjoy the fucking ride down and shut up.”

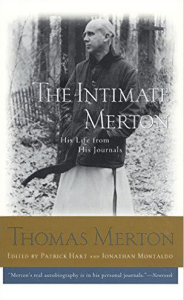

So, looking back, to finally answer your question, my favorite work is the project Brother Patrick took up to give the publisher an “anthology” that combined the seven volumes of Merton’s journals into one volume. We produced a book of seven chapters that corresponded to each volume, which was highly edited, and I made that transparent to the reader in my introduction. It was the most enjoyable project I’d ever undertaken. I made my own path through the woods of Merton’s journals to produce, The Intimate Merton: His Life from His Journals.

So, looking back, to finally answer your question, my favorite work is the project Brother Patrick took up to give the publisher an “anthology” that combined the seven volumes of Merton’s journals into one volume. We produced a book of seven chapters that corresponded to each volume, which was highly edited, and I made that transparent to the reader in my introduction. It was the most enjoyable project I’d ever undertaken. I made my own path through the woods of Merton’s journals to produce, The Intimate Merton: His Life from His Journals.

Although I would go on to present Merton’s writing in many guises, volumes like Dialogues with Silence: His Prayers and Drawings, A Year with Thomas Merton, and Choosing to Love the World: Notes on Contemplation, I am most grateful to Brother Patrick for allowing me to produce with him my “intimate” presentation of who Merton was in the light of my own reading and my personal life’s perspective on who he was.

Along the way, have there been times when you found yourself too consumed with Merton and losing yourself?

The short answer is never. I never tire of reading and speaking about the values I have discovered in listening to Merton’s “voice.” His text has been my mentor, and in his texts I have discovered abiding consolation at having fucked up on my way forward to becoming a deeper and more inclusive human being. His texts have been mirrors for me.

As Merton artfully discloses his own struggles, I have sensed that my own struggles to become a deeper and wider human being, living expansively with more courage, honesty, and joy, are the real stuff of the “spiritual” life.

Merton has taught me that I shall always be a novice, every day beginning again, and that, no matter what actions I take to care for my interior life and serve my neighbors, I shall always have to kneel and wait for a mercy that I know by my own experience (and Merton’s, embedded in his text) I can never give to myself. I’m thinking of the end of Bernanos’ Diary of a Country Priest as I write this, which ends with the priest’s recognition that he must be content with who he really is: “I am reconciled with the poor, poor shell of me. All is grace.”

Are there any thoughts you want to share about living the spiritual journey?

No. What thoughts I have put in writing about “the spiritual life” are to share my reception of Merton’s lived theology manifested by his writing, all of it—the journals, the spiritual reflections, the letters, the poems, political manifestos, his calls to social justice and non-violence.

But if you asked me to come clean, it’s the autobiographical writing that has taught me most. When Merton speaks most personally, he speaks most universally. I “get him” and “get myself” when he drops the pose of holy monk and tells his reader how it is with him.

Merton’s autobiographical writing, what he called his “art of confession and witness,” has been the vehicle (the great raft) for me, and hundreds of thousands of other readers discovering themselves in his artful disclosure, of a “way” forward through the darkness and the joy of being alive and awake throughout the total catastrophe of being a human being. His autobiographical writing is a testament to his compassionate transparency to his reader. “You’re in a lot of shit, reader, and so am I, but there are so many possibilities for creative contemplation and action when you stay on the road toward joy.”

You’ve recently turned seventy. What’s most important for you now?

I always end my retreats the same way. I say aloud that, “If there is one thing I have learned from Thomas Merton, it is that one can write and speak beautifully about the spiritual life without actually living a beautiful spiritual life. So I ask you, (sometimes my voice quivers, but mostly I hold it together when I come to this plea) that as you leave this room, please pray for me that someone like me who dares to present ‘ideas’ about the spiritual life in public, not in the end himself be lost.”

I want, if I can, to finally stand on my own two feet now and, in the words of Mary Oliver, “let my soft body love what it loves.”

I have spent decades looking with a jaundiced eye at institutionalized religious life, sneering at the very idea of the search for God and holiness. I realize (I had this “epiphany” just last week in Assisi) this has been my defense mechanism to keep at bay my abiding disappointment with myself that I was unable, because of so many fissures in my character, to live the life I had envisioned for myself when reading Silence in Heaven.

Yes, I have always wanted to be a monk, but my character has not made it possible. I do think that the old forms of the institutionalized monastic life (there are experiments everywhere) are on the slope toward extinction. The Abbey of Gethsemani will one day be a truly experimental monastic community open to the world or it will become a “Trappistland,” something like a “Shakertown,” where hired actors (young) sing in choir seven times a day. And at 2:00 PM every afternoon, a visitor can attend a Trappist funeral as a mannequin clothed in Cistercian robes is lowered into the ground, no dirt finally spread since tomorrow is another performance. This is not to say that American Trappist life since the mid-1850s has been in vain. Many a man and woman have been saved by the Rule of Saint Benedict, and the Cistercian charism in particular.

But a tipping point has been crossed, it seems to me. The old veterans are mostly left, and the ones I know strike me as deeply expansive, compassionate, joyous human beings. They are full of generosity, motivated by an appreciation of their own humanity and everyone else’s. The times, however, do not favor carrying on in quite the same way for those coming up now. They will find their own paths, some of them formal to be sure, but in ways that will be different from the kind of monastic life Merton loved but knew and foresaw that eventually must be fruitfully transformed.

Personally, I am learning to die well. I am training myself for when the time comes, and who knows if it’s soon, perhaps tonight, when it’s over. I would like, if I’m conscious, to die with tears of gratitude for all the blessings I’ve received through so many who have loved me in spite of myself and, more miraculously, have loved me in spite of themselves. I want to die, if I’m conscious, assuring anyone holding my hand, even if it’s a strange nurse—let her be gay, please, but I prefer a “she” in any case—not to be sad. I am telling myself over and over again these days, in training, that all has been grace. I hope, as I succumb, that, like a drowning man, my whole life and the persons in it will pass before my eyes. And, in the words of Mary Oliver, I realize with gratitude that I “haven’t just visited this world.”

Personally, I am learning to die well. I am training myself for when the time comes, and who knows if it’s soon, perhaps tonight, when it’s over. I would like, if I’m conscious, to die with tears of gratitude for all the blessings I’ve received through so many who have loved me in spite of myself and, more miraculously, have loved me in spite of themselves. I want to die, if I’m conscious, assuring anyone holding my hand, even if it’s a strange nurse—let her be gay, please, but I prefer a “she” in any case—not to be sad. I am telling myself over and over again these days, in training, that all has been grace. I hope, as I succumb, that, like a drowning man, my whole life and the persons in it will pass before my eyes. And, in the words of Mary Oliver, I realize with gratitude that I “haven’t just visited this world.”

Jonathan Montaldo

November 6, 2015

Rome, Italy

Jonathan can be reached at jonathan.montaldo@gmail.com, and for further info please visit: www.MonksWorks.com.

Jonathan Montaldo is an exceptional person who is just entering another growth period.

He not only has done a great service to Thomas Merton and his admirers, which are legion,

but he has been so incredibly helpful to those like myself who have written essays, etc. on

Merton. He may be 70, but at 74 I envy his dedication, his energy, his travels and above all his spirit which will always be young–with the wisdom that comes with age for people like him. Thanks, Jonathan.

Wow! What an interesting journey explained by Jonathan Montaldo about what lead him to this love of Merton. I believe I would like to know more about the man behind the Merton journals. There seems to be so much more to him than what is presented on other web sites.

Understanding how and why someone is lead to do what he or she does, is in fact, what I identify with. As he goes through his journey from seminarian to soldier to editor, to speaker, and then writer – I am inspired.

What draws me to Merton is his humanness; what draws me to Montaldo is the journey that he shares.